The 80 John Story

Early Days on the O’Daniel Plantation: 1860-1875

Daniel Webster Wallace was born in Victoria County, Texas on September 15, 1860, the son of William Wallace and Mary Barber, both slaves on the O’Daniel plantation. About three months before his birth, his mother had been sold to the O'Daniel family and he grew up with the O'Daniel sons, M.H. and Dial, and he remained in close contact with them and their family all of his life.

After amusing himself with stick horses on the dirt floor of his family’s tiny two room cabin, Webster grew quickly and when ready for school, was a large boy for his age – long and lanky, but with the earliest signs of a coming manly sinew and stature. As a young boy he had an aversion to the school in the wintertime and his job chopping cotton the rest of the year. Always known to be a dreamer, at every opportunity he watched and listened as the ranch’s cowboys plied their trade in the distance of the property, longing to also rope and ride horses and work cattle. In 1875, at age 15, he stealthily ran off and begged his way onto a cattle drive as a spare hand, chuck wagon wheeler and fledgling horse wrangler. Although completely new to riding, he was a natural around horses, and he quickly mastered the art of riding, roping and performing all of the duties of a trail-driving cowboy, quickly developing a reputation as a highly reliable, and skilled young cowboy and budding ranch hand.

Riding the Range: 1875-1885

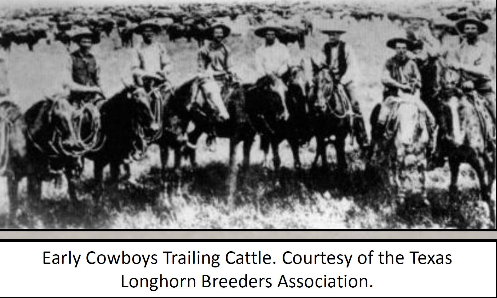

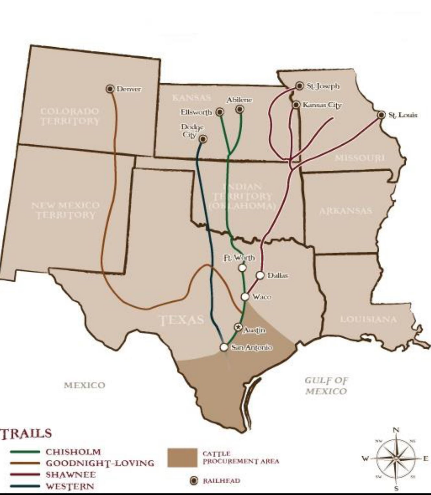

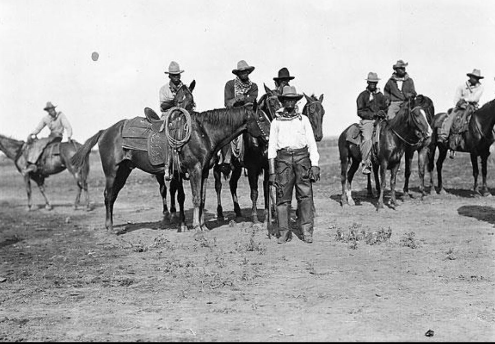

In the 30 years after the end of the Civil War well worn cattle drive trails developed taking cattle up from the Texas prairie to the railroad shipping points in Kansas, Colorado and Missouri to service the insatiable Eastern demand for beef. The most famous trails, the Chisholm, Goodnight-Loving, Shawnee and Western and their spur trials saw millions of head of cattle move north, and every drive required large groups of skilled cowhands. Throughout this period it was common to see expert Black and Mexican cowboys working herds, even groups consisting entirely of cowboys of color.

Young Webster rode for the most famous and respected cattle barons of these seminal days of the Texas Cattle industry, including C.C. Slaughter, Isaac L. Ellwood, Andrew B. Robertson, Sam Gholson, and C. A. "Gus" O'Keefe. He also rode for the Bush and Tillar Cattle Company and worked for John Nunn’s “N.U.N.” cattle outfit on the headwaters of the Brazos River as a wrangler and horse breaker – a skill for which he was said to have had no peer. He rode every major cattle trail for these icons, from the Chisholm Trail to the Goodnight-Loving Trail. He made long, daring solo rides for them, and had harrowing adventures, including wild stampedes, dangerous river crossings, deadly Comanche raids and brutal snowstorms in Texas, New Mexico and Old Mexico. He won unwavering respect for his cowboy skills, cattle knowledge, fearlessness, personal code of ethics and innate intelligence. Moreover, he won their trust for his high character, integrity, and, eventually, his innate business savvy.

As a young cowboy he worked hard, early, and late, learning the finer skills of cattle herding from the older men. He often drew some of the most difficult and dangerous work, taming wild horses. He was thrown a lot but treated it as a test of wills and would always say “Bring him back again, let me try him again…” Typically, his indomitable spirit and stubbornness outlasted the horse or at least tired them into temporary submission.

He was also the wrangler for the outfit, trailing the unsaddled horses nearly all day and at night he had to be sure they didn’t wander off from camp. He had to awaken the cook, then ride each cowboy’s mount for a few minutes to get the bucking out of him. He hated it but came to be as good a rider and horseman as any of the experienced cowboys.

Bill Nunn had one of the largest spreads in Texas, claiming over 8,000 head of cattle. Working with him, young Webster as he was then known, had some of his most exciting experiences on the range as they drove herds into Brown County, known to be dangerous Comanche territory, an area east of the Pecos River known as "The Concho". The Comanche were known to raid, kill the men, steal teams, burn the wagons and scatter the cattle. On one particular trip several of Webster’s fellow cowboys rode too far from camp and were overtaken by Indian raiders, with one boy killed. Webster and other cowboys spent several days finding their horses and traveling back to camp.

Life on the range was hard, lonesome work and Webster sometimes felt alone, having no friends to turn to for understanding, but he suffered no racial indignities or epithets and gradually came to form fast and deep long-standing friendships among his cowboy co-workers. Some of these old friendships came into play much later in his life.

The range was a man’s country where Webster grew and matured as a young man during this period. In addition to his riding and horse breaking skills, he mastered roping, even the dangerous trick of roping buffalo. He participated in spring and fall deliveries, branding, watching for cattle thieves and Indians, finding mavericks and breaking wild horses.

He watched but didn’t participate in the cowboys’ heavy drinking, poker, craps, pranks and mock trials. His principles, seriousness and rugged individualism would not allow such hi-jinx. As a testament to his skills, character, honesty and his bosses total trust in him, he was often tasked with delivering the full cash or gold proceeds of major cattle sales back to the home ranches in long, multi-day solo rides – never failing to deliver a single, hard-earned penny.

Working for Clay Mann: 1885-1891

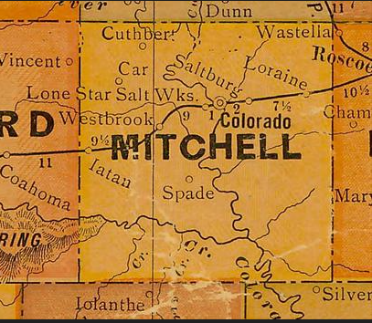

Cattlemen in need of cowboys for a drive often simply approached cowboys who seemed out of work and hired them on the spot after a few questions to discern their experience and claim of previous employers. Cowboys who sought work would be hired with few questions asked when ranchers came up shorthanded on the eve of a drive. Cowboys like Webster, who could claim having worked for well-known cattlemen like Sam Gholson and Bill Nunn were highly valued, quickly hired and paid well. Upon arrival in Buffalo Gap, young Webster sought out one of Texas’ best known cattlemen, Clay Mann, to hire on. Mann had extensive holdings in Mitchell, Kent, and Coleman counties in Texas, as well as Endee, Ft. Sumner and Portola counties in New Mexico and in the State of Chihuahua in Old Mexico. He always had large herds on the move, employed hundreds of cowboys, and paid his best cowboys well. Over the next several years Webster would become Clay Mann’s best and most trusted hand, and they would develop a friendship that fostered Webster’s attainment of his ultimate dream – to become a landowner and a true Texas Cattleman. Along the way he traveled with Mann to his many, vast ranches on his explorations and drives. He was exposed to every phase of early day ranching and mastered them in anticipation of someday working for himself.

It was branding Mann’s cattle with a large “80” on one side that gave Wallace his well-known nickname of “80 John”. As a cowboy he experienced adventures beyond his wildest dreams. On long trail drives, traveling to and from the ranch and when scouting, as he often did alone, Webster carried a six-shooter in a holster and a Winchester rifle wrapped with his bedding on his horse. He had used them in self-defense along the trails, but spoke little of it. He rode the range lines in eastern Mitchell County and on the Double Mountain Fork and the Yellow House prong of the Brazos River, an area which had been the site of desperate battles between buffalo hunters and Indians in 1877. He rode and scouted for Mann down in Old Mexico, at his Bovito Ranch (later sold to William Randolph Hearst), nearly dying in an Indian raid, and barely making it back to Mitchell county.

His favorite horse was a pony he called “Peck”, because he said, “He was no bigger than a half a bushel”. But Peck had a big heart and great instincts with cattle. He was a top cutting horse and could cut out any cow in the herd without a bridle. His instincts meshed perfectly with 80 John’s cutting skills and he seemed to know when to crowd in, working an animal out of a herd and turning him back when he had pushed it far enough.

Having little formal education, at age twenty-five he returned to winter school down in Navarro County, was admitted to the second grade, and in two winters learned to read and write. There he met and courted a young teacher, Laura Owens, convinced her to marry him and they returned to West Texas, his homestead land, to start what became a loving and fruitful marriage of 51 years, bearing them four children, many grandchildren and great success as West Texas ranchers.

Whenever Clay Mann had to travel away from the ranch he tasked 80 John with running the ranch and watching over Mann’s wife and children during his absence. After Clay Mann’s passing in 1889, 80 John continued to assist Mrs. Mann in managing the large ranch, and he was also given the important responsibility for taking Clay Mann's two young sons under his wing to train them in the art of riding and other cowboy skills and the fundamental techniques and business principles of ranching.

Becoming a “Cattleman”: 1885-1899

From the start of their relationship, Clay Mann had taken note of 80 John’s great intelligence, work ethic, and his growing thirst for knowledge about the cattle ranching business. Together they implemented a plan in which Mann paid Wallace only five dollars of his thirty-dollar monthly wage for a period of two years, putting the remainder aside to invest in his own herd, for which Mann provided free pasture. This working relationship nurtured a bond of mutual trust and respect which lasted until Mann’s death in 1889.

By 1885 Wallace was ready to start ranching for himself and purchased his first land southeast of Loraine in Mitchell County. In addition to working for Mann he did extra work in town in Colorado City, took the savings from his town work and used it to purchase steers, some of which he soon sold for a profit of sixty dollars – money he poured back into growing his herd. He had started down the path of becoming one of the most successful and respected ranchers in the area and one of the most successful black ranchers of his time.

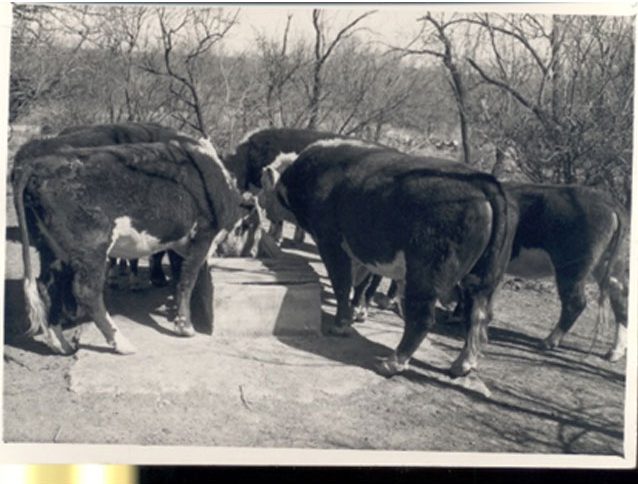

In 1891, two years after Mann’s passing, 80 John and Laura moved their cattle to their now 1,280 acre ranch property, built their original homestead house and commenced their career as full time cattle ranchers. His Durham cattle brand was a D triangle; on his Herefords he used a D on the right hip and a running “W” on one side. With Laura by his side, Wallace began to methodically build his herd, utilizing his learnings and experiences with Clay Mann and the other wily old ranchmen. He began to cobble together his dream of being a full-fledged Cattleman - he had the land and began to acquire more and more cattle. Laura was his life and business partner, assisting him with all business transactions and legal contracts, and with handling all ranch management by herself for long periods when he was away on a long cattle drive or on other ranch business, including for one whole year as he drove their herd to New Mexico in search of adequate pasture during a long West Texas drought. They endured these frontier hardships to build a successful ranching business that grew to over 8,800 acres and 500 head of cattle through hard work, sacrifice and their widely-acknowledged progressive ranching practices, including the area’s first windmill. They grew a family and fostered in them a love of education and an understanding of the need for taking leadership roles in their community. And above all, they fostered a love for the soil of West Texas, ensuring that their ranch land and cattle business remained in family hands…and it still does today, over 140 years after their initial homestead was established.

Successful Family Man, Businessman and Philanthropist: 1900-1939

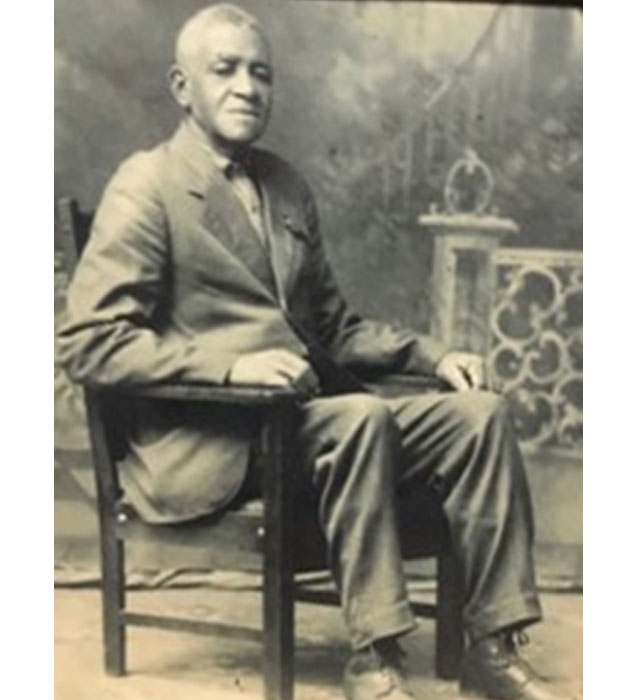

80 John Wallace was a natural born leader, the very personification of a rugged individualist, who led by example in a time when little opportunity for high achievement was afforded the formerly enslaved and their descendants. As a result of his passion for cattle business, work ethic, wise and progressive business practices and personal philosophy of life, on his passing, at age 79 in 1939, as the Depression continued, he had no debt and was worth over one million dollars.

Moreover, he was noted for sharing his skills, wisdom and bounty with all, leaving his West Texas community with his indelible mark of integrity, progressive ranching methods, a focus on education and lending a helping hand for upliftment to black and white alike. From the 1890’s on he and Laura utilized lawyers for all major business transactions and developed family estate trusts still in effect to this day. Valuing education above all, they sent their children and grandchildren to colleges including Northwestern University, the University of Colorado, the University of Chicago, Prairie View University and Texas College. He built local schools and churches in Mitchell County and was revered for his great recall and extensive knowledge of the County’s history, and the wild and exciting days of the Texas cattle industry centered around Colorado City, a major cattle drive center and eventually an early hub for rail shipments from West Texas to the major cattle markets.

Daniel and Laura are buried on the first section of land they acquired, nearby the homes they built for their family. Their descendants still live on and run the family’s Mitchell County ranch today, and in 2014 they donated the original circa-1890 homestead house to the Texas Tech National Ranching Heritage Center in Lubbock, where it has been lovingly restored by the Museum and is displayed as a tribute to 80 John and Laura's vision, tenacity, resiliency and achievement.

80 John was a knowledgeable and highly respected member of the Texas Cattle Raisers Association for over thirty years and was a fixture at their meetings, which he attended regularly. He often rode the segregated train to Ft. Worth for the Association's statewide meetings. On one such trip, a group of Wallace's early-day cowboy and rancher friends came back to the colored section of the train to talk with him as these trips provided the longtime friends with a rare opportunity for lengthy conversation. Under the rules of segregation at the time, after allowing them their talk for long periods, the conductor would tell the white men to move back to their coach. On one such occasion a long-time friend made no effort to move, stating to the conductor:

"I have known John for thirty years. We ate and slept on the ground together. I see no reason that makes it impossible for me to sit here with him now."

And there he remained - such was the depth of friendship and true bonding these men had attained in their cowboys and ranchers on the trail and in business, through good times and bad. And there perhaps, is the defining element of the 80 John story…the bonds of friendship, common struggle and the interdependence of West Texas cowboy life overcame the burden and impact of historical racial and social divisiveness otherwise present in their times.

Daniel Webster Wallace prided himself on never needing, seeking or receiving aid from the government during the depression. In addition, he was not compelled to sign waivers on his cotton crop. However, he did sell seventy-five head of cattle to the government in the Great Round-Up. By 1936, at the height of the depression, it was said by the locals that Wallace, in a quite matter of fact tone, would say that he “owned fourteen and one-half sections of land and six hundred head of cattle”, and he meant it quite literally. There were no loans, mortgages, past due taxes or financial encumbrances of any kind to overshadow his ownership - he was a millionaire with no debt.

His acts of charity were legion and were always quietly done - he always gave money to promote the welfare of his fellow man and civic welfare. He gave to his church and built a school for the local Negro community and as well as another local church. He bought wares from the crippled and blind, paid more than their price, and then returned their goods for another sale; and he never left a beggar hungry for food. Friends came from far away to ask for assistance in buying homes, which he gave them in a businesslike way that protected him. Upon sale he often let the owner keep all proceeds, foregoing repayment.

He cherished formal education and sent his children and grandchildren and also many other unrelated youths to college. In homage to his hard-scrabble roots and cowboy and cattleman relationships, 80 John kept close track of the financial affairs and wellbeing of old friends, white and black, who had assisted him in the early days and if he found they were in need, he was always there with unsolicited cash aid, earnestly and gratefully proffered.

A 1936 article in The Cattleman Magazine about 80 John wrote that:

"…he spoke in a deferential manner and in language wholly lacking in Uncle Remus dialect..."; old timers and young people liked to hear him speak authoritatively about their cattle country as he first saw it and rode it, more than a half century before, "...unsullied by barbed wire...a cowman's paradise of running water, grass-covered hills and fertile valleys"

In 1939, at the age of seventy-nine, 80 John Wallace was still quite active despite his age. He would ride two hours daily on his favorite mount, Blondie, a beautiful horse with a long mane and tail that almost touched the ground. Blondie was a wonderfully smart cow pony that instinctively knew when to slacken or tighten the rope. Still loving the feel of the saddle at seventy-five, he would show young men how to ride a wild horse in the streets of Loraine, the small town nearby the ranch. Even after he built a beautiful modern home for his beloved Laura in 1932, he often preferred to sleep in the nearby bunkhouse, which reminded him of his long-ago cowboy and homestead days.

In his later years he was visited regularly by surviving members of the O'Daniel and Mann families, who came to check on him, wish him well and give him an opportunity to talk about the "old days" on the trail with his friends. In his foggy reverie, he sometimes spoke of his days with his little friend Dial, the O'Daniel son whom his Mother, Mary, had nursed alongside him, slave child and master child. The Wallace, O’Daniel and Mann families maintain contact and hold close friendships to this day.

On March 28, 1939 Daniel Webster Wallace, known to all as "80 John" used his last breath to call out to his beloved Mother and tell her he was coming to join her. And he slipped away, leaving a legacy of tenacity, hard work, business intelligence, vision, charity, love for family and, above all, high character, for all who knew him or know of his story.

He has a Texas State Historical Marker on the ranch, and has a Texas Trail of Fame Star Marker at the Ft. Worth Stockyards. In 2014, the original homestead house was completely refurbished and moved into display at the National Ranching Heritage Center at Texas Tech in Lubbock and the “80 John” story is in most Texas history schoolbooks. His ranch in Mitchell County, including Silver Creek, remains intact and has been continuously worked and lived upon for over 130 years by a member of the Wallace family. It is held in a trust set-up by 80 John and Laura and remains undivided to this day. It has not been a working cattle ranch for decades but the land is leased for grazing, grows cotton, has oil exploration, and wind turbine power generation. It sells water to local municipalities and hosts oil pipelines from the nearby Permian Basin oil patch. Proceeds from the ranch have continued to fund the education of all Wallace descendants wishing to attend college – many generations have done so under 80 John & Laura's proud and watchful eyes.

His nature and character were imbued with an unrelenting competitive spirit and drive to accomplish the most he could, despite being born a slave; overcoming childhood adversities and handicaps; lack of money; droughts; infestations; blizzards; dust storms; badlands; bandits; and Indian wars - he persevered, kept his focus on his dream and became wildly successful in his chosen field. By Texas’ unique standards, his spread was small, but to him it was big as all outdoors - and most importantly, was bought and fully-paid for by the sweat of his brow and allowed him to raise his children, see them flourish and contribute to his community. 80 John Wallace had the pleasure of seeing his Texas-sized dreams come true.

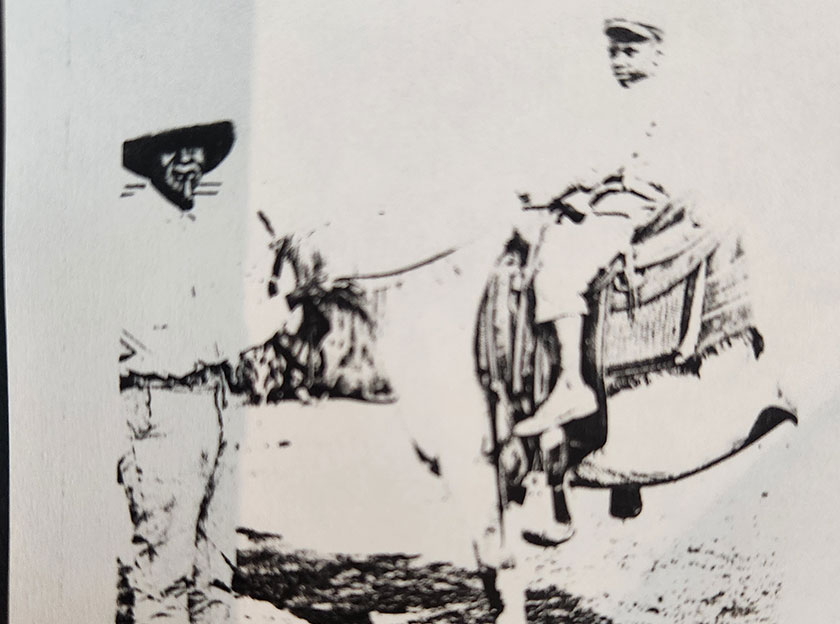

80 John Standing with Grandson, D.C. Fowler